"Half the time I was a different person"- A psychologist's journey with PMS

- Ellen Lambert

- Feb 15, 2023

- 5 min read

Growing up, I was never taught much about periods or the female anatomy… and I was certainly never taught about mental health issues related to the menstrual cycle.

I’m a Trainee Clinical Psychologist at the Institute of Psychiatry, Psychology and Neuroscience at King’s College London, studying how the menstrual cycle influences emotions, thought patterns, and behaviours in hormone-sensitive women and AFAB (assigned female at birth) individuals of reproductive age, with premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD).

Back in my early 20’s, when I started to experience shifts in my mood and anxiety levels, I felt confused and out of character. Of course, at this point, I hadn’t made the connection that these mood shifts were happening every month in the week before my period. All I knew was that half the time I felt like myself, and the other half I was a different person, and I couldn’t work out why.

That ‘different person’ was full of anxiety. They didn’t want to socialise, they’d cancel plans at the last minute, and they’d be impatient and easily irritated. I’d do my best to ignore that person, trying to bring out the ‘real me’ and hide away the other. I’d enjoy the weeks where I felt confident, motivated, sociable, and generally at ease, but inevitably weeks would come where I’d shut down and try to avoid everything.

I wondered if the stress and anxiety, along with the physical shifts I was experiencing, were just a product of starting my first job and getting older. But the sudden shifts were making me feel increasingly out of sorts, and I would feel embarrassed and ashamed of things I’d said and done.

My Lightbulb moment

Years passed where month after month I’d do my best to manage and mask things. I saw my GP who offered to prescribe me anti-depressants and refer me to psychological services for social anxiety disorder, but neither treatment felt right for me — they didn’t feel like they were targeting the root of the problem.

So, I struggled on, with my alter ego in tow.

I can’t remember exactly when I started connecting my difficulties to my menstrual cycle, but when I did, things really clicked. I do remember reading an article about Premenstrual Disorders (PMDs) on the National Association for Premenstrual Syndromes (NAPS) website, after which I decided to start tracking my menstrual cycle and mood over consecutive months.

A few months in, things started to make sense. I noticed fairly quickly that my mood would drop, and my anxiety would increase in the 7 days before every period. And it was a very consistent pattern. I went back to the GP with my tracking data in hand, and they agreed, it looked like severe PMS.

PMS — of course, I’d heard the term. But what was severe PMS and what could I do to get things under control?

Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS) and Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD): What’s the difference?

Nearly all reproductive-age females experience the menstrual cycle, and despite what the media might try to tell you, most actually do not experience cyclical changes in their moods, cognition, and behaviour. However, a minority of females (approximately 6%) do experience very impairing hormone-related changes in mood and behaviour that only occur in the weeks before their period (DSM-5 Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder or PMDD).

The key difference then between PMDD and other psychological disorders is that for people with PMDD, when they are not premenstrual, they’re totally symptom free, whilst for people with other affective disorders, their symptoms might worsen premenstrually (something called Premenstrual Exacerbation), but they don’t disappear during the rest of the cycle.

Relative to PMDD, a larger proportion of women (roughly 15–20%) experience milder premenstrual symptoms, leading scientists to believe that PMDs likely exist on a continuum, where the severity of cyclical mood change can be totally absent, mild, moderate, or severe.

Receiving a diagnosis

To receive a diagnosis of PMDD, strict criteria must be fulfilled.

Women need to show, via daily ratings of symptoms, that at least one of their cyclical symptoms is emotional (e.g., mood swings, sensitive to rejection, anger, irritability, conflict with others, depressed mood, hopelessness, feelings of worthlessness and guilt, anxiety).

They must also show that five or more physical or behavioural symptoms are present premenstrually (e.g., decreased interest, concentration problems, lack of energy, increased appetite, sleep problems, feeling overwhelmed, breast tenderness, muscle pain, bloating, weight gain).

For a diagnosis of PMS on the other hand, criteria suggests women need to show via daily ratings of symptoms that at least one physical or psychological symptom is present premenstrually, is causing significant distress, and subsides within 4 days of the period starting.

The causes of PMDs

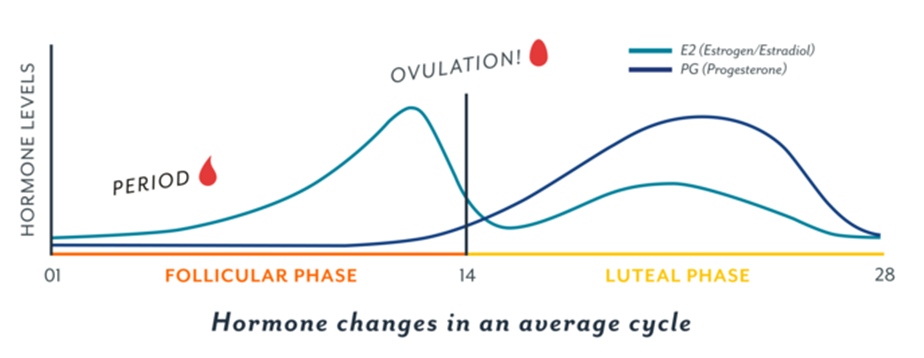

Researchers are actively trying to find out more about the causes of PMDs. Clearly, the timing that the symptoms switch on and off in PMS and PMDD suggests that hormone changes across the menstrual cycle are a key part of the explanation.

However, what is surprising is that people with PMS and PMDD don’t appear to have different hormone levels or patterns or hormone metabolisms compared to people totally absent of any premenstrual symptoms.

Instead, scientists think that women with PMS and PMDD may have an altered neurobiological sensitivity to normal hormonal fluctuations that occur during the menstrual cycle, and that this sensitivity likely exists on a continuum. This could explain why we see some women totally absent of premenstrual symptoms, some who experience mild or moderate difficulties, and some whose symptoms are so severe that high rates of suicidal thoughts, self-harm, and suicide attempts feature.

Treatment options

Researching what we know so far about the causes of PMS and PMDD helped me normalise my own experience, and better understand what was going on in my brain and body that meant I was changing so much premenstrually, while others I knew seemed to get by without many difficulties.

In terms of first-line treatment options, I found that a huge focus was on medication such as hormonal birth control or antidepressants, as well as advice around lifestyle change. I also know that for many individuals with PMDD, who have often gone through the exhausting process of trialling the above options, that referral to a gynaecologist and hormonal and surgical treatments are usually explored next.

At no point in my own journey was I offered psychological therapy for my difficulties. Even now, although guidelines state that CBT should be considered routinely as a treatment option, the treatments available are likely to be generic CBT techniques, rather than a more personalised treatment that truly takes into account the multifaceted nature of PMDs.

From my own perspective, despite there being no official evidence base for their use, I have found techniques from Dialectical Behavioural Therapy and Compassion Focused Therapy to be helpful for emotion regulation and reducing self-criticism during the premenstrual phase.

Ongoing research and PMS

Premenstrual disorders represent an important public health problem, and much more can be done for women living with these difficulties. Psychologists don’t routinely receive basic training in this area, but I believe that psychological professionals are in an excellent position to acknowledge PMDs and provide support.

Furthermore, psychologists can initiate more research into psychological factors involved in PMDs, so that future psychological treatments can be adapted to specifically target the key mechanisms at play.

As part of my own research at King’s College London University, I’ve recently launched a new study looking into how we process and think about our emotions across the cycle. We’re currently recruiting women with mild, moderate and severe PMS (including diagnoses of PMDD).

If you are living with PMS or PMDD and you’re interested in supporting research I would love to hear from you. Please don’t hesitate to get in touch, by following us on twitter (@PMSEmotionStudy) and emailing me at ellen.r.lambert@kcl.ac.uk